Piano Factory 10.

|

Grant Chu Covell [November 2013.]

Sergei ZAGNY: The Well-Tempered Clavier (2013); Pieces Nos. 4-4a (1991). Sergei Zagny (pno). FancyMusic Fancy015 (1 CD) (http://www.fancymusic.ru/). This recording documents an installation of Zagny playing a quirkily tuned upright set beneath a swinging lamp, part of the sculpture Die Kunst der Fuge by Vladimir Smolyar. Videos show wires and what looks to be a modified bicycle wheel suggesting an airborne Duchamp. Alongside Zagny’s gently wandering preludes (there are 12 of them) we hear a gentle strumming much like a radiator in the room next door, altogether describing a fragile interior scene. Sometimes the mistuned piano resembles clattering bottles. There are three versions of Piece No. 4 and two of 4a. Also captured under the oscillating lamp, explorations in different registers.

Jürg FREY: Klavierstück 2 (2001); Les tréfonds inexplorés des signes pour piano (24-35) (2007-09). R. Andrew Lee (pno). Irritable Hedgehog IHM 006 (1 CD) (http://www.irritablehedgehog.com/). Despite the program note’s alert, the repeated chord dominating Klavierstück 2’s center will astonish. After a few minutes of generously spaced somber chords, the clarion perfect fourth shines like a beacon. The 468 repetitions permit reveling in piano resonance. Eventually, you may wonder how it will all end. Anticipation and dread are unexpected responses to such an ostensibly straightforward work. The repeated chords are followed by different material, and when the music finally concludes at 15:20, you may wonder whether you imagined those fourths. The 12 pieces in this section of Les tréfonds move cautiously yet confidently across austere spaces. Some offer repetition. Whether a garland of repeated intervals or a stepwise maneuver, each motion counters expectation. Lee plays evenly and earnestly. While it may be counterintuitive to put “Wandelweiser” and “exciting” in the same sentence, it really is exciting to see the Wandelweiser collective attracting committed advocates.

Jacques CHARPENTIER: 72 Études karnatiques pour piano (1957-84). Michael Schäfer (pno). Genuin 12257 (3 CDs) (http://www.genuin.de/). A gigantic wheel explores the Carnatic ragas (Karnakangi, Rhâtnangi, Gânamurti, etc.). Charpentier works freely with the modes, taking cues from the permitted pitches. Aptly dedicated to Messiaen, there’s a bit of virtuosic Liszt and Ligeti, and in some cases, Tom Johnson’s additive gestures. Some études suggest Debussy’s Préludes, others reflect American minimalism, jazz or Andriessen. Most are decisive bursts around the two minute mark, but not all. Each six-étude book can be taken as an independent suite as the pieces alternate moods and tempos. Occasional insertions of a few six-movement suites might make a preferred experience. The 12th and final book permits an open form structure calling to mind Cage or Stockhausen. Schäfer resolutely probes hills and valleys, a devotion that pays off: a gigantic and dynamic achievement (61:00 + 51:50 + 66:09).

Anton BATAGOV: Selected Letters of Sergei Rachmaninoff (2013). Anton Batagov (pno). FancyMusic Fancy026 (1 CD) (http://www.fancymusic.ru/). Rachmaninoff had no interest in the avant garde yet Batagov asserts that Rachmaninoff’s emotive tonality, often revolving around a few pitches or chords, is the antecedent for several minimalist and quasi-minimalist composers. Batagov’s inventive fantasies blend Rachmaninoff with Simeon ten Holt, Peter Gabriel, Arvo Pärt, Ludovico Einaudi, Philip Glass, Wim Mertens (using the well-worn theme / harmony from Paganini’s 24th Caprice), Brian Eno, and Vladimir Martynov. These missives aren’t spoofs, or “in the style of” pieces. For some, the references are fairly obvious, e.g. Eno’s Music for Airports, whereas for others, like the letter to Pärt, the recipient’s style is difficult to find. Regardless, each of the eight creates a distinct mood and style, from the grand epistle to Glass to the perky, abruptly concluding note to Mertens / Paganini. The series is wrapped with two contemplations At the Grave of Sergei Rachmaninoff (this most Russian composer is buried in Valhalla, New York) enhanced with reverb and resonance.

“The Complete John Cage Edition, Vol. 49: The Works for Piano 9.” John CAGE: Haiku (1950-51; ed. Don GILLESPIE); Sixteen Dances (1950-51; ed. Walter ZIMMERMANN). Jovita Zähl (pno), Thomas Meixner (perc). mode 259 (1 CD) (http://www.moderecords.com/). In its more familiar guise for flute, trumpet, percussion, piano, violin and cello, I find Sixteen Dances insipid. Zimmermann’s solo-piano edition, reconstructed from sketches, casts a different light on these 50-plus minutes. Zimmermann and Zähl’s labors convince me that this piece was originally conceived for piano. It’s now possible to hear the dissonances and abrupt dynamics in the context of Music for Changes. Perhaps it even reflects Boulez’s influence (via Tudor). I more and more believe that the instrumental version is a miscalculation. Not to be confused with the Seven Haiku from about the same time, these Haiku are tiny variegated bits, with slight repetitions. Two additional Haiku, recent discoveries both, are included for good measure. In the Dances Zähl is captured up close so that rambunctious attacks resonate. The 16 enjoyable movements sound like dances, with a percussionist joining in two alternate versions of XV and XVI.

“The Sudden Pianist.” Michael HERSCH: Suite from the Vanishing Pavilions (2005-11). Michael Hersch (pno). Innova 859 (1 CD, 1 DVD) (http://www.innova.mu/). This 23-part Suite, an abridgement of a two-and-a-half hour original, sounds like improvisation despite its hour length. I imagine Hersch noodling until the sun sets and the neighbors complain. The accompanying notes compare this music to Messiaen, Sorabji and Finnissy. Despite the music’s obvious difficulties, it doesn’t seem untowardly complex despite hot flashes and car crashes. There’s little to suggest a centrality despite the affinity with Christopher Middleton’s poetry. Perhaps I’m missing the point. I did appreciate a disc of orchestral works and explored the DVD of Richard Anderson’s 29-minute biopic and a video of the CD’s Suite performance. Hersch discloses more about circumstance and results and less about motivation and intention. One enjoys watching blazing hands even if the gestures are unfathomable. It does impress that he memorized the thing. Hersch is known for his prodigious memory.

Valentin SILVESTROV: Naïve Musik (1954-55; rev. 1993); Der Bote (1996-97); Two Waltzes, Op. 153 (2009); Four Pieces, Op. 2 (2006); Two Bagatelles, Op. 173 (2011); Kitschmusik (1977). Elisaveta Blumina (pno). Grand Piano GP639 (1 CD) (http://www.naxos.com/). Approaching the piano music after the grandiose symphonies, a listener is better prepared to understand Silvestrov’s nostalgic Romanticism. Otherwise, how could we accept Naïve Musik’s Schubert, Grieg and Chopin gestures? Blumina plays liquidly, keeping much of the irony to herself. However, for Der Bote, a strange Mozartian exhalation, Blumina takes the plunge. When the music is explicitly contorted as in the Four Pieces with their wrong-key after-effects, she is equal to the challenge. Where others might dwell on the strangeness or sentimentality, the pianist starts from convention. I am not convinced that this straight-ahead Kitschmusik is what Silvestrov had in mind, with its garden paths leading to bricked-up doors. The Op. 153 waltzes with stunted bittersweet melodies, dedicated to Blumina, receive their premiere recordings. Recently, Silvestrov has taken to bagatelles, with the Op. 173 pair as a kind of premiere. Rest assured, there will be more sad music.

John CORIGLIANO: Winging It: Improvisations for piano (2008)1; Chiaroscuro (1997)2; Fantasia on an Ostinato (1985)3; Kaleidoscope (1959)4; Etude Fantasy (1976)5. Ursula Oppens1,2,3,4,5, Jerome Lowenthal2,4 (pno). Cedille Records CDR 9000 123 (1 CD) (http://www.cedillerecords.com/). Oppens champions a program as varied as one could hope for. Winging It contains three notated improvisations, a bit more extroverted than the similarly tricky five-etude Fantasy of some 30 years before. Classic ostinatos as in Beethoven’s Seventh spark an inventive fantasia combining aleatoric sections with minimalism. The piece I put first on my list is Chiaroscuro for two pianos tuned a quarter-tone apart. Beyond a multi-harmony Ivesian universe are uniquely expressive chromatic lines with in-between notes and charged clusters. I come back to this one for its ingenuity and luscious sound.

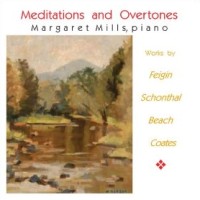

“Meditations and Overtones.” Joel FEIGIN: Four Meditations from Dogen (1994); Variations on Empty Space (2008). Ruth SCHONTHAL: Sonata Breve (1972). Amy BEACH: Five Improvisations, Op. 148 (1934). Gloria COATES: Sonata No. 1: Tones in Overtones (1972). Margaret Mills (pno). Cambria CD-1195 (1 CD) (http://www.cambriamus.com/). This plays as an odd sort of program wherein Mills charts less explored waters. Despite heartfelt aims, Feigin’s Meditations are bland, and the Variations, meant to commemorate the composer’s mother, come across as hollow. Schonthal’s six-minute mid-century modern Sonata aligns with the Classical tradition despite contortions. Beach’s pieces, anchored in Brahms, suggest an awareness of jazz, Orientalism, and Schoenberg. With its overt exploration of octaves, white notes, glissandos, inside piano sounds and heavy pedal, Coates’ innovative Sonata makes for an approachable kooky piece.

Batagov, Beach, Cage, Coates, Corigliano, Feigin, Frey, Hersch, J Charpentier, Schonthal, Silvestrov, Zagny

[More Grant Chu Covell, Piano Factory]

[More

Batagov, Beach, Cage, Coates, Corigliano, Feigin, Frey, Hersch, J Charpentier, Schonthal, Silvestrov, Zagny]

[Previous Article:

Gunar Letzbor’s early Biber]

[Next Article:

Acoustic Revive’s RAF-48H Air-Floating Board]

|