Mostly Symphonies 37: Luc Ferrari’s Histoire du Plaisir et de la Désolation

|

Grant Chu Covell [September 2020.] “The initial idea of this piece is to let oneself go to the harmonics of the devil and the pleasures of sensuality. Pleasure is a journey that goes from logically linked ideas to the breakdown of logic that allows desire to express itself. But the path is paved with desolation, which defeats pleasure.”

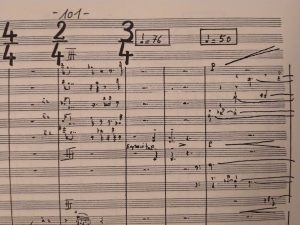

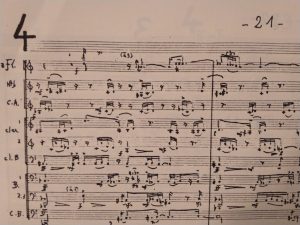

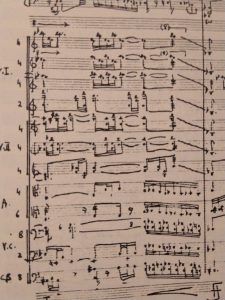

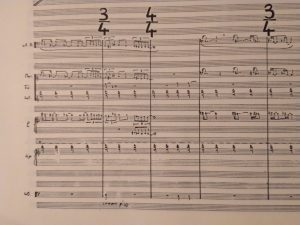

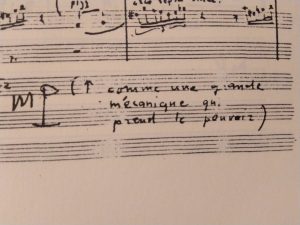

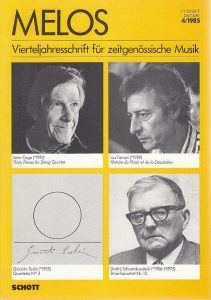

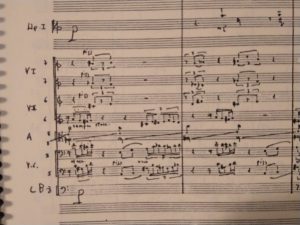

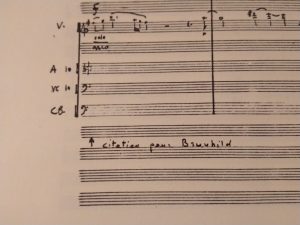

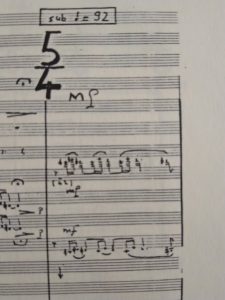

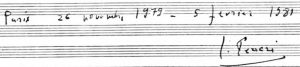

Luc FERRARI: Histoire du plaisir et de la désolation (1979-81). Scored for 4 flutes (2 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 English horns, 3 clarinets (#3 doubling bass clarinet), 1 bass clarinet, 3 bassoons (#3 doubling contrabassoon), 1 contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 tenor trombones (#3 doubling bass trombone), 1 bass trombone, 1 contrabass tuba, timpani, percussion, piano, celesta, 2 harps, 14 first violins, 12 second violins, 10 violas, 10 violoncellos, 8 double basses. Commissioned by Radio France for the Orchestre National de France. Published by Salabert. Appears on: “Matin et Soir,” Adda 581156 (1989): Michaël Luig conducts the Orchestre National de France. CD also includes À la recherche du rhythme perdu (1978) with Henry Fourès and Carlo Rizzo, and the concrete work J’ai été coupé (1969). “Far-West News: Episode N° 1,” Signature SIG 11014 (2001): Same forces as above and presumably the same performance. Release includes the radiophonic Far-West News: Episode N° 1 (1999). Performances are infrequent. The Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra under Johannes Kalitkze was to have played it on June 19, 2020. Page 2 from Symphonie inachevée. We do not think of Luc Ferrari as a composer of symphonies, but he incorporated the designation into several orchestral pieces: Symphonie inachevée (1963-66), Symphonie déchirée (1994-98), and Morbido Symphonie (2005; unfinished). His most effective symphonic work is perhaps Histoire du plaisir et de la désolation (1979-81) which is not labelled as a symphony, although it does bear comparison to the wild, free-form opium dream of Berlioz’ Symphonie fantastique (1830), and more contemporaneously, to the dramaturgy of Berio’s Sinfonia (1968-69). (I say perhaps because of these three named symphonies, I’ve only heard Symphonie déchirée and seen the score of the aleatoric Symphonie inachevée.) Commissioned by Radio France for the Orchestre National de France, the score of Histoire du plaisir et de la désolation offers the dates November 26, 1979 to February 5, 1981. It was premiered November 6, 1982 by the Orchestre National de France, led by Michaël Luig. A recording (Adda 581156) with these forces was released in 1989 which won the Serge and Olga Koussevitzky International Recording Award the following year. The same conductor, orchestra and timings appear on Signature SIG 11014 from 2001. Neither release indicates the performance date or venue, so presumably both recordings are of the 1982 premiere. There are three movements played without interruption: Harmonie du Diable, Plaisir-Désir, and Ronde de la Désolation. The piece takes about 35 minutes. The orchestral work is fully composed. There is no improvisation. There are no tape or electronic components. (Ferrari’s website offers cumbersome English translations: “The Story of the pleasure and the desolation,” and the three movements: “The devil’s harmony,” “Pleasure-desire,” and “Round of desolation.”) Page 1 of Histoire du plaisir et de la désolation. Stylistically, Histoire is post-modern, neither tonal nor atonal, with short thematic motives which recall, sometimes explicitly, other music. These recurring ideas are not developed traditionally but are sequenced to magnify contrasts. The orchestral style recalls big turn-of-the-20th-century scores, notwithstanding the extra percussion. The orchestra is enormous, with quadruple winds, and doublings that emphasize lower registers (two bass clarinets and two contrabassoons are unusual). Ferrari says that he listened to a lot of Ravel, Debussy, Stravinsky, Bartók and Prokofiev while working on this piece. These influences are hard to pinpoint, except perhaps that the wind writing connects with Stravinsky’s early ballets. In Histoire’s universe it is as if serialism and klangfarbenmelodie never existed. Ferrari appears to ignore Stockhausen and Nono’s mid-century structures, although he will appropriate their colors and grand gestures. At various points, I hear affinity with Boulez’ sensual grammar, even though Ferrari is far less complex and layered. I admit my particular interests, but Histoire could be programmed comfortably alongside Feldman’s Coptic Light (1986). Page 10, showing increasing decoration of the held B-flat and E. Let’s first consider Histoire as a tone poem, less along the lines of R. Strauss or Liszt but more like the Debussy triptychs. True to its title, Harmonie du Diable initiates a tritone conflict. We start with a unison low E, somberly repeated, decorated with filigree. Eventually the orchestra switches to a B-flat, similarly festooned. As the flourishes increase, the meter grows unstable, percussion interferes, and a climax builds which is not completely resolved at the start of Plaisir-Désir where a quartet of bongo drummers takes over. Plaisir-Désir contrasts the rapid samba rhythm established by the drum quartet with a slowly moving melody, but continuously interrupts itself with mundane dances (tonal, ethnic or antique parodies) including a caricature of the Allegretto from Beethoven’s Eighth. Ferrari’s pacing is masterful as chips of the percussion patterns are taken up by different instruments. The central movement builds to a climax through layering and abrupt contrasts, eventually reaching a series of repeating chords which dissolve inconclusively into the Ronde de la Désolation. First appearance of “desolation,” marked “Expresif,” played by the clarinets as two chords, on Page 101. A forlorn gesture becomes the Ronde’s focus. Elsewhere this material appears as the piano piece Vue sur la désolation from Fragments d’un journal intime (1980-82) but here it is entrusted to clarinets, sometimes with harp. Bits from Plaisir-Désir’s ramp-up intrude, but “desolation” persists. The orchestra attempts several derailments that remind us of the late-20th century. There’s a suggestion of the Dies Irae, but the clarinets win out and the piece trails off inconclusively. Desolation has triumphed over pleasure, or perhaps desolation is the inevitable result of the pursuit of pleasure. The clarinets have the last word, on Page 157. It is not clear when this recording was made, but I presume we hear the premiere. Ferrari has specified details that are inaudible: subdivided strings and winds, frequent grace notes and glissandi. Around culminations, Ferrari’s thick and chaotic textures drown out individual voices, but there are plenty of pages where primary and secondary voices are not balanced. Then there are pages which are frankly intended to be chaotic, where we realize Ferrari has been paying attention to contemporary trends. However, the big, dramatic gestures come through: tempo changes, massed percussion, assertive tuttis. The performance hangs together even though we might not hear everything. String and wind details which are hard to discern (Pages 21 and 22). Given Ferrari wrote little for orchestra, let’s consider Histoire as musique concrète and as an embodiment of his tautology technique. The Tautologos series occupied Ferrari in the 1960s and resulted in pieces or events where actions framed by silence were repeated with slight modifications. This process suggests something akin to minimalism, but Ferrari uses fully fleshed out motives, and the results focus more upon larger repeating patterns like the way the time of sunset changes a bit each day. Ferrari would have preferred to frame the tautology technique in terms of repetitions. Each movement varies a basic formula: Two opposing ideas are repeated separately, progressively developed through shortening, ornamentation or lengthening, and eventually overlapped and combined. True to its name, Harmonie du Diable juxtaposes E and B-flat; the second movement contrasts non-pitched rhythm against a slower melody with interrupting tonal dances; in the last movement lyric and non-lyric material battle. At the opening, the E is orchestrated in unison with all instruments playing the pitch for the same duration, but eventually this unison breaks down when the instruments repeat the pitch at different rhythms. The initial 4/4 meter and four-bar phrases become forgotten, yielding constantly changing time signatures (5/16, 1/4, 5/8, etc.). The two pitches E and B-flat are treated as sampled events and developed independently in successive loops which gradually overlap creating tension. This design appears in the brief Strathoven (1985), a tape piece which intercuts Stravinsky (Firebird) and Beethoven (Symphony No. 5), and reaches a culmination using a rapid echo technique before dissolving into completely different material for a brief coda (the ambient sound of movers at work). The percussion quartet in Plaisir-Désir establishes an aggressive atmosphere. The interrupting tonal dances are carefree, and they start and stop abruptly as if spliced into the insistent drumming. Rhythm and melody are developed separately and then simultaneously as in a collage, leading to a passage of chords accelerating like a machine spinning out of control. In both Plaisir-Désir and Ronde harps set off climaxes and signify changing direction. The Ronde juxtaposes the sweetly maudlin clarinet trio against the angry full orchestra. Ferrari’s tautology technique involves gradually introducing more of the clarinet idea at each restatement alongside a parallel development of the orchestra’s non-thematic outbursts. Material will change abruptly like a tape splice. Orchestral patterns will accrue and become loops, and Ferrari indicates “like a mechanical giant who takes power.” The clarinet theme eventually incorporates a sweet transformation of the Dies Irae, as if that is where we were heading all along. As a further illustration of intertwined contradiction, the clarinets’ idea follows a 4/4 pattern but is notated in 3/4. The clarinets hold out against fewer orchestral interruptions, but they break off unresolved. One of the interruptions (“Citation pour Sophie”) which has a stereotypical Oriental character (Page 70), and Page 119: “like a mechanical giant who takes power.” Page 29 (which suggests Boulez), and Page 84 (which chaotically jumbles motifs). Cover of Melos, April 1985. Cage, Scelsi and Shostakovich make great company. In April 1985, the journal Melos published Klaus Hinrich Stahmer’s article, Vom Vergnügen an der Lust (“From Pleasure to Lust”). Stahmer’s article drew upon multiple sources, including a July 14-15, 1984, conversation with the composer, the program for Histoire’s premiere, one of Ferrari’s cheeky biographies (Autobiography No. 11), etc. Stahmer offers a traditional analysis with diagrams and examples which interweave among the elusive interview and Ferrari’s vivid but unreliable texts. As I’ve tried to do here too, Stahmer considers Histoire as both orchestral tone poem and as symphonic realization of musique concrète. As we should expect in a good analysis, he proceeds measure by measure diagramming order slipping into chaos and noting the details. A diagram from Stahmer’s analysis of the first movement. Stahmer and the composer are keen to categorize Ferrari’s styles up until 1984 into phases: a black period, a red period (although red begins in 1963 and black ends in 1967 so they overlap), and by the time of the article, a blue period (“blue like the Mediterranean”). These phases regularize influences (serialism, etc.), but now in retrospect, they are hard to discern except as curious boundaries applied within a world where it was difficult to get information. There’s no doubt that Stahmer admires the piece, comparing it to Debussy, identifying orchestral timbres which connect the Ronde de la Désolation to traditional Todentanz and tarantella-like music of Liszt et al. Stahmer also presciently sees Histoire as documentation of a journey, citing the tape piece Music Promenade (1964-69), etc. The radio travelogues were yet in the future, although other pieces were well known by this time, such as Presque Rien (1967-70) with its sounds of sunrise at a beach, in which superimposed vacation recordings create a particularly pungent memory. From Page 64, an example of Ferrari splicing interrupting material within a waltz (“Citation pour Mara”) using tempo indications to indicate different material. Note that the 10/4 measure is actually 10/8. In her preface to Ferrari’s Complete Works (Ecstatic Peace Library, 1999), Brunhild reveals that the theatre piece Journal Intime (1980-82; for piano, actress, vocalist and tape) “analyses and charts” Histoire, and that its themes were drafted in notebooks. As already observed, Ronde’s clarinet motif appears in Journal Intime’s recomposition for solo piano, Fragments d’un journal intime. (Journal Intime is discussed here.) In Complete Works, Histoire’s title is translated as “A History of Pleasure and Desolation” in one place and “A History of Pleasure and Distress” elsewhere. Brunhild also discloses that Ferrari suffered from dystonia, or writer’s cramp, as far back as 1965. She says that writing out instrumental scores was agony for Ferrari, that this pain is visible in Ferrari’s handwriting, and that this is why Brunhild’s handwriting often appears in his scores. In the diary he kept specifically to chronicle Histoire’s composition, Ferrari doubles down on several preoccupations which were also vividly explored in Journal Intime, especially duality and the simultaneous combination of opposites. Histoire is emphatically concerned with contradictions: A tritone is defined by two incompatible pitches (E and B-flat), rhythm vs. melody, order vs. chaos, pleasure vs. desire, male and female, etc. Details from Pages 110 and 117 which are unfortunately hard to hear in the recording. We don’t have a complete picture of Ferrari’s music if we ignore sex. Several pieces are explicit: Pornologos 2 (1971), Danses organiques (1971-73), Sexolidad (1982-83), Chansons pour le corps (1988-94). (In Chansons pour le corps, a clarinet pair provides the treble voices. Coincidence or significance?) Histoire suggests sex with its movement titles. The arrangement of opposites could reflect male vs. female; although the arrival and retreat from musical climaxes could specifically suggest foreplay and orgasm. When Ferrari suggests he was listening to a lot of Ravel, Debussy, Stravinsky, Bartók and Prokofiev during Histoire’s creation, could he have been revisiting Daphnis & Chloe, Jeux, The Rite of Spring and the Miraculous Mandarin? (I admit not being able to find an early Prokofiev ballet which depicts sex.) It would also be possible, in a traditional analysis which Ferrari would have rebuffed, to consider some ideas masculine and others feminine. However, I prefer to summarize an idea incorporated into Journal Intime: Ferrari believed that when he was composing, he was exploring his feminine side. In the second movement which contrasts simpler dances against percussion, a male-female conflict can be identified. I can see late 20th-century theorists getting all excited over textual evidence. The interrupting tunes which Ferrari calls “Citations” each acknowledge a woman: “Citation pour Brunhild,” “Citation pour Jacqueline” (the Beethoven parody), “Citation pour Mara,” “Citation pour Sophie,” and “Citation pour Anne.” In an email conversation I had with Brunhild in November 2016, she recalls that these were the names of their closest female friends at the time. “Citation pour Brunhild” on Page 44, and part of “Citation pour Jacqueline” parodying Beethoven (Page 55). It may be best to consider Histoire autobiographically: “I wanted to deliver myself to the ‘harmonies du diable,’ and to savor the pleasure of my sensations,” wrote Ferrari. “Pleasure, desire, the frustration of pleasure, the appearance of despair and desolation… these conflicts, these lack of arrivals, thwarted expectations are all variously expressed and realized in Histoire.” Ferrari’s signature and date at the end of the score (Page 157).

[More Grant Chu Covell, Mostly Symphonies]

[More

Ferrari]

[Previous Article:

Music in the Midst of the Plague: A Conversation with Beth Levin]

[Next Article:

Used Bin Troll Tweets RR.]

|