My Favorite Morricone

|

Grant Chu Covell. [August 2020.]

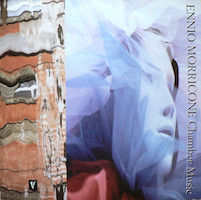

On news of Ennio Morricone’s passing (July 6, 2020), I did not revisit The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966), nor did I succumb to the charms of Cinema Paradiso (1988). Instead I sought out Suoni per Dino (1969; published by Salabert in 1973), a brief, inscrutable eight-minute concert piece. My favorite Morricone appeared in 1988 on a Virgin CD (7 90996-2) titled simply, Chamber Music. Set aside the cover’s dreamy Venetian Carnival. The sixth track appears after several self-explanatory items: a Sestetto (flute, oboe, bassoon, violin, viola and cello), Musica per 11 Violini, 3 Studi (for flute, clarinet and bassoon), Ricercare (for piano), and 4 Pezzi (for guitar). The disc concludes with Distanze, a piano trio. Suoni per Dino is different because in addition to the stringed instruments we hear percussion and a complex chime. These sounds, a two-note drum beat and a chord, repeat at just enough distance so that they are hard to predict even though they occur regularly. The drum’s two notes suggest a dominant-tonic but not quite. The complex chord, high and brittle, could be celeste, vibraphone, or synthesizer. Eventually, the first stringed instrument appears offering held notes, then another with higher pitched fidgeting, and then a third and fourth and so on, gradually increasing the texture until the process reverses, leaving several long and high pitches over the distantly spaced drum and chime. In actuality, the work is a canon for a single viola with live processing and pre-recorded tape (the drum and chord). A second tape recorder captures the viola and delays it so that the single performer plays over himself. The entire opus is limited to four pitches, A, Db, D and Eb. The drum plays the descending tritone Eb-A, but because these are synthesized tones, they sound similar enough as to gently confuse whether we hear high-low or low-high. Equal attacks perpetuate the ambiguity: A human performer would invariably accent one or the other (either iamb or trochee), even if subtly. The chord is all four pitches at once. The Db-D-Eb cluster is not as dissonant as it may appear on paper because of the treble pitch and the light reverb. Drum and chord alternate at five-second intervals (quarter-note = 60) which is not terribly slow, but the precisely noted viola entries obscure the beat and most of us are not used to counting in five. Listeners probably won’t perceive the work’s constraints, that there just four notes, that there is only one live player (with at least one technician). Overall, the piece resembles an arch, beginning and ending with the same percussive sounds, as the stringed instrument(s)’s pitches migrate from low to high. As the composition progresses, the early viola gestures are lost to tape decay. Because the viola finishes in its top register, it’s easy to think there are multiple instruments. The single-page score (which unusually reads from bottom to top) can be found in Alessandro De Rosa’s Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words (Oxford, 2019). There are 16 lines of music each taking 30 seconds. Morricone precisely describes the work, which even included a lighting plan (because in concert, it would be clear that one musician was being duplicated by tape). Deriving melodies from a narrow range of pitches was a technique Morricone also employed in his film scores. Speaking with De Rosa, Morricone says: “I realized that by using generative cells of maximum seven tones, a wider audience would be able to follow my ‘musical discourses’ with ease, especially when those cells were derived from Greek, Hebrew or other ancient modes.” The recording quality of Sestetto and Musica is fairly dim, suggesting these might be older tapings, or hastily assembled studio readings. The CD release offers no notes, just track names. Suoni per Dino was written for Dino Asciolla, a violist who worked with Morricone in several productions. Asciolla eventually joined the Quartetto Italiano. He is not credited on this recording, but I presume that’s who is playing. Suoni per Dino stands out from the rest of this release’s modernist explorations (Morricone studied with Petrassi). The tape effects may pass unnoticed, but the symmetrical shape does not. From my first encounter, I heard something mysterious in the drum and the doorbell-like chord. Not only is this my favorite Morricone, it’s perhaps one of the best compositions to use only four pitches.

[More Grant Chu Covell]

[More

Morricone]

[Previous Article:

How to Practice During a Pandemic II]

[Next Article:

String Theory 32: Quartets, plus or minus]

|