Italian Vacation 13.

|

Grant Chu Covell [April 2016.]

“Dulle Griet.” Giovanni VERRANDO: Dulle Griet (2010); Third Born Unicorn, remind me what we’re fighting for (2009); First Born Unicorn, remind me what we’re fighting for (2001); Quartetto No. 3 (2003); Second Born Unicorn, remind me what we’re fighting for (2002); Il ruvido dettaglio celebrato da Aby Warburg (2002); Triptych #2 (2008). Mdi Ensemble, RepertorioZero, Pierre-André Valade (cond.). Aeon AECD 1328 (1 CD) (http://www.outhere-music.com/). In Verrando’s universe, noise enriches but does not obliterate. Considering these works chronologically reveals noise staking a claim as an independent voice. Most of these pieces require amplification, and Verrando may incorporate non-standard sounds, for example, manipulating sheets of paper, or, as found in Triptych #2, churning marbles in a parsley chopper. Previously considering Verrando’s orchestral works on Stradivarius, the comparison with Romitelli was easy and inevitable. However, Verrando is not just about including electronics because it’s au courant. These pieces establish a framework for embracing details, as in the title piece, Dulle Griet (cf. Bruegel’s painting) which is predominantly quiet. Verrando starts with deep rumbling and then progresses to hypersensitive amplification of otherwise small gestures. The three Unicorn pieces, for flute (First Born…), piano (Second Born…) and violin (Third Born…), encircle their instruments with varying weights of noise. At times they too will be calm, although the violin does occasionally step forward to imitate a metal sander. The piano solo Second Born… reappears in Il ruvido dettaglio celebrato da Aby Warburg. The title (“The rough detail celebrated by Aby Warburg”) explicitly refers to the art historian who said that “God is in the details.” The Third String Quartet is one of the few items not to require electronics. It is an intense delicate quivering two movements of fragile tremolos and hesitant arpeggios. Chords and perhaps actual phrases appear to repeat in the later ensemble works.

Bruno MADERNA: Requiem (1946). Diana Tomsche (sop), Kathrin Göring (alt), Bernhard Berchtold (ten), Renatus Mészár (bass), MDR Rundfunkchor Leipzig, Robert-Schumann-Philharmonie, Frank Beermann (cond.). Capriccio C5231 (1 CD) (http://www.capriccio.at/). Maderna was compelled to serve during WWII in Mussolini’s army, but in the last months of the war fought for the Italian Resistance. The Germans caught and detained him at Dachau. During these years (1944-46) Maderna completed a Requiem: “At that moment, it was the only possibility to write a requiem and then to die.” If this didn’t have Maderna’s name on it, we probably wouldn’t be treated to this 2013 recording. The piece had been lost until 2009 when it turned up in the United States, where it had been shelved after Virgil Thomson’s attempt to broker a performance came to nothing. Even realizing this is Maderna before Darmstadt, serialism and polystylism, this is a particularly curious specimen. Scored for soloists, chorus, strings, brass but no winds, three pianos and percussion, the mass setting (nine movements in two parts) swirls through a full gamut of mid-century styles that aren’t serial and aren’t aggressively dissonant. Stravinsky, Bartók and Hindemith might be starting points; however, the 26-year-old Maderna harkens back to the massed forces of Verdi and Berlioz. It is a mature one-hour composition confidently demonstrating choral mastery, counterpoint and fugal writing. Nono had seen the work when he was studying with Maderna and observed the master’s skill. There are unexpected effects as in the Dies Irae when the solo tenor and bass are supported with solo strings, and also expanses (Sanctus) where Les Noces and Symphony of Psalms are nearby. This piece suggests that serialism’s supremacy was inevitable.

“Music in Two Dimensions: Works for Flute.” Bruno MADERNA: Musica su due dimensioni (1952)1; Divertimento in due tempi (1953)2; Concerto per flauto e orchestra (1954)3; Musica su due dimensioni (1958)4; Honeyrêves (1961)5; Cadenza da ‘Dimensioni III’ (1963)6; Serenata per un satellite (1969, arr. Roberto FABBRICIANI)7; Per Caterina (1963, arr. FABBRICIANI)8; Serenata für Claudia (1968, arr. FABBRICIANI)9. Roberto Fabbriciani1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9, Luisella Botteon7 (fl), Massimiliano Damerini2,5,8,9 (pno), Alvise Vidolin1,4 (sound direction), Orchestra Filarmonica “G. Monaco,”3 Marcello Panni3 (cond.). mode 260 (1 CD) (http://www.moderecords.com/). Collected in one place, Fabbriciani and friends provide Maderna’s complete works for flute and then some. Fabbriciani picks up where Severino Gazzelloni, the dedicatee and first performer of most of these pieces, left off. The tiny Honeyrêves for flute and piano is quite captivating once you know the title is essentially “Severino” spoken backwards. The title Musica su due dimensioni was affixed to two different works. Both have a pre-recorded component, but the tapes are different and each is supported with different ensembles. The initial Musica was among the first to combine live performer with tape, even though its original version was for flute and cymbals (imagine a Stockhausen castoff). The later Musica asks the flute player to make performance decisions, and the playback engineer may do so as well. Three arrangements appear for the first time: Serenata per un satellite for multiple flutes, and the two single-minute miniatures which Maderna penned for his daughters, Per Caterina (flute replacing violin, with piano) and Serenata für Claudia (flute replacing violin, piano replacing harpsichord). The Serenata really was written for a satellite, ESRO 1B, “Boreas,” launched October 1, 1969, from Darmstadt, Germany.

Daniele VENTURI: Quattro lembi di cielo (2003-05)1; Preludio all’infinito silenzio… (2007-08)2; Planto (2006)3; Charanam (2007)4; Agnus Dei I (2005)5; Bagliori (2005)6; Trois très triste (2007)7; Angeli che avete bisogno del suono (2007)8; Transfigurations (2008)9; Il mare è tutto azzurro (2007)10; Lai (2007)11; Tratti sospesi (2007-08)12. Raffaello Negri1 (vln), Duo Novecembalo2: Chiara Agosti (fl), Diadorim Saviola (hpsi), Nicola Baroni3,5 (vlc), Fabiana Ciampi4 (hpsi), Barbara Vignudelli5 (sop), Antonella Guasti5 (vln), Monica Moroni6 (fl), Enrico Calcagni6 (ob), Paolo Panigari6 (clar), Alessio Pisani6 (bsn), Francesca Salvemini7 (fl), Alessandro Carmignani8 (c-ten), Paola Perrucci8,12 (hrp), Fausto Caporali9 (org), Ensemble vocale Arsarmonica10, Duo Dissonance11: Roberto Caberlotto, Gilberto Meneghin (accordion). Bongiovanni GB 5161-2 (1 CD) (http://www.bongiovanni70.com/). These 12 fine pieces, not quite miniatures, come together as a string of gems or stories in a series. Sometimes the instrumentation is non-standard: flute and harpsichord for Preludio all’infinito silenzio…, accordion duo in Lai. The presence of a piece for organ, Transfigurations, almost justifies the intent of a home recording; however, because there is an Agnus Dei for soprano, violin and cello, and a piece addressing angels for countertenor and harp, Angeli che avete bisogno del suono, we could just as well be in a sacred space. Some of the titles indicate Venturi is mindful of his country’s musical legacy, the exotic or single words suggest Scelsi and Donatoni, the poetic lines referencing silence and sea could be Nono or Sciarrino. Indeed, Venturi gently introduces us to precious things, to show we are on secure footing. Each piece proceeds deliberately with sensitive economy. When the flute player in Trois très triste sings, this is not for effect but a logical progression. The set is framed with larger solos for violin, Quattro lembi di cielo, and dissolving harp, Tratti sospesi. The Quattro lembi di cielo are engrossing, and in gentle defiance of the program which Venturi has built, I have replayed them independently.

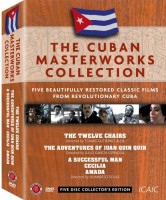

Humberto SOLÁS: Un hombre de éxito (“A successful man”). (1986). Available in The Cuban Masterworks Collection, Instituto Cubano de Arte e Industria Cinematográfica. ICAIC 720229912532 (5 DVDs) (http://www.cubacine.cult.cu/). Luigi Nono’s Das atmende Klarsein (1980-83) makes appearances in Solás’ 103-minute history about two brothers navigating the Cuban revolution. One is idealistic while the other is opportunistic. What can possibly go wrong? Nono receives a prominent music credit at the start, even though the score is predominantly popular tunes. The eerie electronically altered flute and chorus appear at moments of emotional weight to underscore the characters’ anxiety and loneliness. Well, I don’t think anyone expects Nono played live at cafés. The credits note Massimo Cacciari’s texts and Roberto Fabbriciani on flute.

[More Grant Chu Covell, Italian Vacation]

[Previous Article:

You Too Can Program Your Local Symphony!]

[Next Article:

The Hemidemisemi-Monde]

|