Farinelli’s Last City

|

Ellen MacDonald-Kramer [April 2017.] [With thanks to Luigi Verdi of the Farinelli Study Centre.]

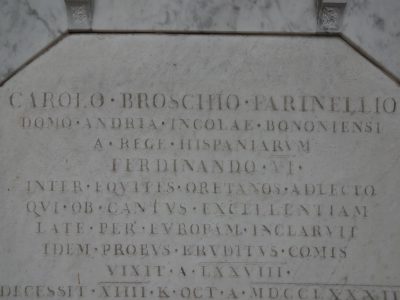

Bologna is a wonderful city on its own merit. Just imagine those distinctive red-toned medieval buildings with their arched colonnades, tortelloni and good wine in cozy osterias, gelato in sunny piazzas. A surprising number of locals own dachshunds. In the centre of town is the massive, strikingly unfinished Basilica of San Petronio. You can’t really go wrong, in this northern Italian city. But at the risk of starting to sound like a travel guide, I’ll admit that Bologna may not have been in my top few European cities to visit if it wasn’t for my fascination with castrati. Paying respects to the final city – and resting place – of the greatest castrato, Carlo Broschi (better known by his stage name, Farinelli) seemed an appropriate pilgrimage, a good reason to go in itself. The Certosa di Bologna rests approximately two and a half miles from the city centre. A former monastery, this extensive arrangement of halls, quads and cloisters has long served as the city’s cemetery. Enter its quiet walls, and you find yourself lost among elaborate tombs, stones, and monuments. The tiled floors are a little uneven; the thought might cross your mind that the graves could cave in and swallow you. Once or twice, maybe, you notice a human figure in the corner of your eye and turn, with some alarm, to see that it’s a life-sized statue in a realistic pose. Grieving widows, characterful angels, loveable children, a breastfeeding mother: all frozen in mourning. It’s a delightfully spooky place. And the Certosa is one of the sites that makes Bologna such a potently musical city. Among the tombs of Bolognese families, you can discover familiar musical names, such as Colbran (Rossini’s first wife, the singer Isabella, is interred here with her family), Adelaide and Erminia Borghi-Mamo (a mother and daughter who led acclaimed operatic careers in the 19th and early 20th centuries), and even the late popular artist Lucio Dalla, among others. But it was to see Farinelli’s grave that I visited the Certosa – twice in one trip, I confess. Farinelli was the most lauded castrato singer of his day. His posthumous reputation is still strong among opera fans and historians; if you’ve ever heard of opera seria and the castrated men (yes, sorry) who first portrayed its soprano heroes, you’ve probably heard of Farinelli. If you can name only one castrato, it’s Farinelli. The Gérard Corbiau film Farinelli was released in 1994, and a play by Claire van Kampen, Farinelli and the King (see my review here) debuted in London in 2015. Farinelli is considered one of the greatest singers in the history of opera. All that – and yet, because he died in 1782, we’ve no idea how he sounded. Numerous contemporary paintings of Farinelli exist, alluding to his celebrated status. At his grave, however, his physical likeness is as lost as his voice. Located in one of the Certosa’s many cloisters, the singer’s place of rest is surprisingly humble. There is no life-sized statue, only a plaque crowned by the carving of a lyre. Carolo Broschio Farinellio, the letters read, and further down, cantus excellentiam. There’s something touching about its simplicity.

Originally interred at the monastery of Santa Croce, Farinelli’s remains were moved to the Certosa in 1810 following the destruction of the former place by Napoleonic forces. He was temporarily exhumed in 2006, for the purpose of researching how castration had affected his bones. The terracotta tiles that now cover his tomb are conspicuously new. Farinelli had performed in Bologna as a young man (he was born in 1705), but it was only in 1760 that he settled there, having just spent more than 20 years at the Spanish court in Madrid. His time in Spain, during which his singing famously proved therapeutic to the depressed King Philip V, is the most heavily referenced period in his life. After commencing his service in Spain, Farinelli never again performed in public, and when he finally returned to Italy, it was to live in retirement. He had acquired land outside the walls of Bologna sometime before moving there, and overseen, from Madrid, the construction of the elegant villa where he would live the last years of his life. The nearby church, at which his funeral took place, is as surprisingly humble as his grave. The villa was sadly demolished in the 1940s, but near its site you can find a city park in Farinelli’s name. The little church is still standing. In the 18th century, Bologna had a thriving musical culture, so it was a suitable place for a retired singer. The city boasted the famous composer (and priest) Giovanni Battista Martini, a close friend of Farinelli’s. A new opera house – today known as the Teatro Comunale – opened in 1763, the previous one having burnt down some years earlier. Farinelli filled his new home with the fine possessions he had acquired throughout his career. He owned many musical instruments, including Stradivarius and Amati violins, as well as several harpsichords which he named – curiously – after Italian painters. He also had a vast art collection which included copious portraits of himself. The contents of his home were dispersed after his death, but one of the most striking portraits can still be seen in Bologna. I went to see this painting, as a natural part of my nerdy pilgrimage. It has a place of honour in the Museo internazionale e biblioteca della musica: a former fresco-filled palazzo that now houses scores, instruments, and likenesses of musical personages, among other artefacts. Looking around the museum, you find busts of Gioacchino Rossini and Maria Malibran; scores in the hands of Rossini and Martini; a letter by Giuseppe Verdi. There are portraits of the composers Cimarosa, Porpora, Scarlatti and Vivaldi, as well as some of other singers, a few of them castrati. But Farinelli’s portrait is by far the most magnificent.

Corrado Giaquinto (1703-1765): Portrait of Farinelli (ca. 1753). Museo internazionale e biblioteca della musica, Bologna, IT, via Wikimedia Commons. Painted by Corrado Giaquinto, it depicts the singer standing before an oval image of the Spanish king, Ferdinand VI (son of Philip V, whom he had initially served) and his queen, Barbara of Portugal. Farinelli wears the mantle of the Order of Calatrava, a knighthood he received during his service in Madrid. It is known that he requested his body to be wrapped in this mantle after death. Unlike many of his contemporary Italian singers, Farinelli was universally liked not only for his voice, but his character. Other starring castrati – the highly paid, doted-upon celebrities of the opera world – were known for being arrogant and temperamental (Caffarelli’s behaviour was considered particularly outrageous). But Farinelli remained seemingly uncorrupted by success, respected for his gentleness and humility. “Hes so civille & well bred too yt makes one like him more [sic],” the Duchess of Leeds wrote to her stepson in 1734, at the onset of Farinelli’s brief period in England. His portraits hint at something of this softness of character, and there’s a consistency to them that gives you a sharp impression of how he actually looked. Through the last years of his life, Farinelli took Mass at home from a private chaplain. He paid visits to eminent persons, received visitors, performed charitable works, played and composed on his many keyboard instruments – and continued to sing, although in private. His life may have been a lonely one despite its apparent liveliness; as a castrato, of course, he had no children to keep him company as he grew old, and would never have been allowed to marry, had he wished it. The English musicologist Charles Burney visited Farinelli in Bologna in 1770, a meeting at which the composer Martini was also present. Burney reported: “Signor Farinelli, pointing to Padre Martini, said, ‘What he is doing will last, but the little I have done is already gone and forgotten’” – a manifestation, no doubt, of the sense of loss felt by all singers whose art predated recording technology. Farinelli must also have been aware that the taste for castrato voices was in decline. By the later 18th century, castrati had begun to be considered less enticing and more monstrous: products of a barbaric practice which, if technically illegal and never publicly condoned in the first instance, further lost its footing with the emergence of Enlightenment ideals. We may not have the voice that made Farinelli famous, but he has certainly not been forgotten. He is celebrated, if you know where to look. That’s a lot to say, of a singer we will never hear.

[More Ellen MacDonald-Kramer, Photo Essay]

[Previous Article:

Piano Factory 19.]

[Next Article:

Odes to Music]

|