EA Bucket 33.

|

Grant Chu Covell [July 2022.]

Bernard PARMEGIANI: Stries (1980; ver. 2014-19). Broeckaert//Berweck//Lorenz: Colette Broeckaert, Sebastian Berweck, Martin Lorenz (synthesizers). mode records 328 (1 CD) (www.moderecords.com). “Mémoire Magnétique, Vol. 2 (1966-1993).” Bernard PARMEGIANI: Témoignages (1972); Pop secret (1970); Voyage conseil (1970); Lion d’or (1988); Flash sports (1975); Spot pub (1971); Journal TV 2 (1981); Stade 2 (1976-86); L’art du monde des ténèbres (1982); Sonal Roissy (1971-2005); Bongo fuego (1967); Electrorythmes (1966); E Pericoloso sporgersi (1991); Une mission éphémère (1993); Une honorable partie de Gô (1978); Sonal Roissy (1971). Transversales Disques TRS22 (1 LP / digital album) (www.transversales-disques.com). Parmegiani’s catalog contains few works requiring live instruments, which makes this work for three synthesizers and tape that much more of an oddity. Back in the day, synthesizers were cranky and unpredictable, but they could deliver if coaxed and treated well. This piece was written for the trio of Yann Geslin, Laurent Cuniot and Denis Dufour who had bumped into Parmegiani during his tenure at INA/GRM in Paris. This piece languished for years until the Berlin-based trio of Broeckaert, Berweck and Lorenz worked with Geslin to reconstruct it. There are three movements: “Strilento,” “Strio,” and “Stries.” The first is about 17-and-a-half minutes of tape alone and can be played separately, in which case it should be called “Adagio.” The second part asks two of the keyboardists to control the left and right channels of the stereo tape. The last movement puts everyone together to accompany the tape. Given the second movement is shortest and calmest, it’s advisable to hear this as a three-movement concerto in traditional fast-slow-fast form. Unless you’re well acquainted with the timbres of the Yamaha CS-40M, the EMS Synthi AKS, or the Roland System 100M, it may be hard to separate tape from synths. The tape reuses transformed violin sounds (created by Devy Erlih) which had appeared in Violostries (1963). In the notes Berweck reveals how reconstructing the original synthesizer’s patches and colors took a bit of effort, and how it might be possible to discern the modern synths’ warmer tones compared to the harder-edged tape. The second movement can be considered as something akin to performers sculpting the fixed tape. The last movement offers more collaboration as the synths deliver fast pitches over the tape’s foundation. It is instructive to contrast Stries with the shorter pieces in the second volume of the Transversales Disques set. Some bits had commercial aims: to introduce radio and tv programs or to get travelers’ attention at airports. Generally, these morsels are traditional, with perky rhythms, recognizable scales and quickly discernible forms and patterns. Flash sports is a humorous etude, and the airport alerts (Sonal Roissy) are time capsules. Bongo fuego is a lively pastiche with a beat. If Stries disrupts the notion of foreground and background, or antecedent and consequent phrases, these pithy items conform to conventional distinctions between melody and accompaniment, high and low, short and long, etc. Parmegiani was fluent across all dimensions and extremes.

David DUNN: Verdant (2021). Neuma 120 (1 CD) (www.neumarecords.org). Dunn’s striking Verdant unveils an immense vista, with birds, slowly moving pastel drones, and a light seasoning of random (or algorithmically generated) blips. For a while, it’s like looking through the wrong end of a telescope, until the details sharpen, and the reframed focus becomes comfortable. It’s long enough (78:44) that it tugs at wanting to be peaceful despite flashes of dark thoughts. During listening it can be easy to confuse moments within the piece (birds, nature) with sounds heard in the listening environment.

“Mirage.” Milana ZARIĆ and Richard BARRETT: Mirage (2020); Restless Horizon (2020); Šuma (2016); Nocturnes (2019); Sphinx (2020). Milana Zarić (hrp, e-hrp), Richard Barrett (electronics). STRANGE STRINGS str01 (digital album) (www.richardbarrett.bandcamp.com). Here is a collection of lush and active pieces for harp and electronics, in which we witness a harp not being a harp because electronics can pull and coax the instrument in various directions. Also, harp strings need not be plucked, but can be rubbed or otherwise set to resonate. Several pieces are the product of improvisation, whereas at least one, Sphinx, is a through-composed electroacoustic piece leveraging harp. In Šuma the harp and the electronics are most evidently separate and engaged in quick repartee, whereas in the newer pieces, Mirage and Restless Horizon, the evidence of practiced collaboration, it is harder to distinguish the individual players. Restless Horizon and Nocturnes require an electronic harp so that the instrument’s sounds can be directly fed into electronics. Nocturnes alludes to Debussy at the start, then enfolds nature recordings and the singing of Zarić and Barrett’s son.

“Elektronische Musik 1987-2018.” Bruno STROBL: weiter, weiter, weiter… Transformationen (2018); GlasSkizze (2000); Gesselkopf (2017); Archeton I (1992); Visby 01 (2012); Hiatus (1987). Austrian Gramophone AG0011 (1 CD) (www.austriangramophone.com). “Electroacoustic Music Vol. 2.” Bruno STROBL: Zungenspiel (2021); Mühlentänze (2020-21); Sägewerk (2020). Austrian Gramophone AG0023 (1 CD) (www.austriangramophone.com). Strobl fashions pocket electroacoustic symphonies from specific sources. In weiter, weiter, weiter… Transformationen, Visby 01 and Gesselkopf a double bass becomes boldly transformed. Strobl obscures his raw ingredients, leveraging reverb and filtering, and providing space for his inventions to resonate. Gesselkopf also includes synthesized sounds. Particular to Gesselkopf is a recurring throbbing which passes through like a storm. GlasSkizze explores the resonance of chiming glasses. Archeton I is a brief (5:18) piece meant to be heard during a ferry ride: electronic glissandos skim across recordings of water. Vol. 1’s conclusion is the oldest in the survey: Hiatus expands the snap of an axe splitting wood to create pointillistic effects. The title refers to the gap made by the axe. Vol. 2’s three pieces are longer, and as equally unconcerned with narrative or dramaturgy. Zungenspiel expands upon a barrel organ’s mechanics and ignores its reedy output. Across linked sections, Mühlentänze considers four ancient water-powered grain mills, and in keeping with Strobl’s methods, the sounds of water or grinding are buried. Repetitive events are obscured, and their timescale is transformed into abrasive gestures. Sägewerk similarly memorializes a sawmill’s ambience, the ringing blade, the harsh zip of metal separating lumber.

“Heterotopia.” Natasha BARRETT: Speaking Spaces No. 1: Heterotopia (2021); Urban Melt in Park Palais Meran (2019); Growth (2021). Persistence of Sound PS006 (1 LP / digital album) (www.persistenceofsound.co.uk). External, outdoor spaces are turned inwards in Barrett’s Speaking Spaces No. 1: Heterotopia. There are no mysteries here other than the unexpected sudden loudness of flying birds or gravel crunching underfoot. The album title, “Heterotopia,” derives from Foucault’s concept whereby particular spaces can be made to feel uncomfortable and extra intense. The notes suggest precision placement of the sounds to simulate real and imagined spaces (production efforts which may be lost over headphones or in basic stereo setups). Urban Melt in Park Palais Meran utilizes loops and layering to create gravity. What starts as a chronicle of outdoor recreation gradually changes perspective. Growth is a brief etude (5:59) created in the studio during the pandemic crisis, suggesting different ways of combining and presenting ideas.

“Krypta.” Jannik GIGER: Orchester (2018); On one or with you? (2020); Carey Mary (2021); Krypta (2019). Kairos Records 0015085KAI (1 CD) (www.kairos-music.com). The electroacoustic medium enables the creation of new worlds from recognizable sources. Some composers eschew references (works created from synthesized material), others enhance the familiar (natural sounds are a common subject). Giger has simulated an orchestral work of about 30 minutes in duration, a large score which except for occasional echo effects unfolds as if it could be played by a real orchestra (it’s no surprise that plans are underway to create a live performing version). Giger’s Orchester can be spooky, with prominent saxophones, prepared piano, hazy shapes and gentle repetition of several-second phrases. Whether live or tape, Giger’s aesthetic and technique makes for a compelling half hour. Giger reminds us that a finished recording represents artifice and an immense amount of behind-the-scenes time (practicing, rehearsing, etc.). The other pieces draw upon aural events which listeners are ordinarily not meant to hear: rehearsal noises and discarded takes. On one or with you? marries a saxophone quartet (XASAX) with a vocal ensemble (thélème) captured during a recording session. Bits of Janequin, lute and sax doodling, and rehearsal conversation loop and fuse into a modern madrigal. Likewise, the brief (4:53) Carey Mary swirls material lifted from “Basel’s first improvisational orchestra” (unorthodoxjukebox o). Krypta returns to a larger scale, leveraging rehearsal outtakes of “great conductors,” mostly German, over a slow-moving foundation of orchestral scraps, thickened with percussion. The conductors’ exhortations (and cajoling) are layered over incongruous orchestral and chorus machinations, sometimes humorously indifferent. We hear an audio version of Krypta. There also exists an installation which broadcasts the conductors from a loudspeaker at the end of an aisle in a church crypt, as if they were sermonizing, with the musicians’ responses distributed around.

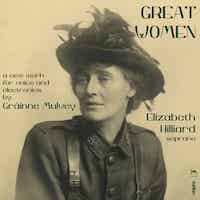

Gráinne MULVEY: Great Women (2020). Elizabeth Hilliard (sop). Métier MDS 29007 (1 CD) (www.divineartrecords.com). Great Women asks us to consider four notable Irish women: Countess Markievicz, Rosie Hackett, Mary Robinson and Mary McAleese. Markievicz and Hackett are represented through their letters articulated by Hilliard. Irish Presidents Robinson and McAleese appear as themselves on the tape. Markievicz was the first woman elected to the UK Parliament (in 1918). Hackett was an original founder and member of the Women Workers’ Union in 1911. The dilemma every composer has when working with speech and electronics is how to balance intelligibility with interesting results. The best parts of Great Women are when Mulvey lets go of the text. We are meant to understand the words, but greater drama and strength is generated when Mulvey and Hilliard let loose.

[More EA Bucket, Grant Chu Covell]

[Previous Article:

Maestro di Suoni e Silenzi: Necessary Nono 6.]

[Next Article:

An Appreciation of Recent Pesson: “Graceless Anticipations”]

|