(Dis)Arrangements 17: Brahms

|

Grant Chu Covell [March 2024.]

“Brahms by Arrangement, Volume One: String Quintets.” Johannes BRAHMS: String Quintet in F minor, Op. 34 (1862; reconstruction by Anssi KARTTUNEN, 2006)1; String Quintet in B minor, Op. 115 (1891; arr. BRAHMS)2. Zebra String Trio1,2: Ernst Kovacic (vln), Steven Dann (vla), Anssi Karttunen (vlc), Krysia Osostowicz1,2 (vln), James Boyd2 (vla), Richard Lester1 (vlc). Toccata Classics TOCC 0066 (1 CD) (www.toccataclassics.com). “Brahms by Arrangement, Volume Two: Orchestrations by Robin Holloway.” Johannes BRAHMS: Variations on a Theme of Schumann, Op. 23 (1861; arr. Robin HOLLOWAY, 2016); String Quintet in F minor, Op. 34 (1862; arr. HOLLOWAY, 2008). Robert SCHUMANN: Six Canonic Studies, Op. 56 (1845; arr. for two pianos by Claude DEBUSSY, 1891; arr. HOLLOWAY, 2011). BBC Symphony Orchestra, Paul Mann (cond.). Toccata Classics TOCC 0450 (1 CD) (www.toccataclassics.com). Johannes BRAHMS: String Quintet in F minor, Op. 34 (1862; arr. Henk DE VLIEGER, 2018); Piano Sonata No. 1 in C Major, Op. 1 (1853; arr. DE VLIEGER, 2017). Orchestre de Picardie, Arie van Beek (cond.). NoMadMusic NMM103A (1 CD) (www.nomadmusic.fr). Perhaps sparked by Schubert, in 1862 Brahms tried his hand at his own string quintet (two violins, one viola, two cellos). Unsatisfied with the format (and undoubtedly incorporating criticism from Clara Schumann and Joseph Joachim), Brahms refashioned the work for two pianos (1863-64, published as Op. 34a) before finally transforming it into a piano quintet (string quartet plus piano, completed in 1864 and published as Op. 34). As a piano quintet, Op. 34’s contrasting colors are equalized. I think Brahms’ ultimate structuring is the best of his three configurations. String quartet and piano can combine and oppose with drama and intensity surpassing a homogenous ensemble. (Not every piano-plus-strings ensemble needs to be about contrast, but Op. 34 demands passion.) Taken together, de Vlieger and Holloway offer a masterclass in orchestration. De Vlieger is more conservative, keeping to techniques Brahms might have leveraged. Holloway’s orchestra is intentionally traditional (eschewing the xylophone Schoenberg added for his piano quartet orchestration) but takes a klangfarbenmelodie approach. Holloway’s Brahms is of this century (or at least the end of the last), wind voicing gently reflecting spectralism, brass alternately punctuating and driving. In contrast, De Vlieger’s decisions acquit themselves well in the Op. 1 Sonata which in this guise bears resemblance to Schumann. After considering other Op. 115 formats (see below), Brahms’ own arrangement (two violins, two violas, once cello) stands on top, perhaps because of these players. This Op. 115 is more jubilant than most original combinations with clarinet.

Johannes BRAHMS: String Sextet No. 1 in B-flat major, Op. 18 (1860; arr. Theodor KIRCHNER, 1883); String Sextet No. 2 in G major, Op. 36 (1865; arr. KIRCHNER, 1883). Matteo Fossi (pno), Duccio Ceccanti (vln), Vittorio Ceccanti (vlc). Brilliant Classics 96867 (1 CD) (www.brilliantclassics.com). Kurt ATTERBERG: Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, Op. 21 (1917-22)*. Johannes BRAHMS: String Sextet No. 2 in G major, Op. 36 (1865; arr. Kurt ATTERBERG, 1939). Truls Mørk* (vlc), The Symphony Orchestra of NorrlandsOperan, Kristjan Järvi (cond.). BIS CD-1504 (1 CD) (www.bis.se). Brahms valued Kirchner’s arrangements. He approved mightily of Kirchner’s piano-trio transcriptions of his string sextets, and asked his publisher Simrock what else Kirchner could have a go at rearranging. A piano trio is easier to assemble than a sextet, and so crafting additional versions for smaller forces was practical and good business. The B-flat sextet is not bad as a piano trio, but Kirchner’s handling of the G-major sextet is miraculous. Brahms’ material endures, but Kirchner’s format permits lightness when the piano takes over. I can imagine Brahms working out the piece on the piano, especially in the slow movements. Atterberg tackled his string orchestra interpretation of Brahms’ second sextet in 1939. Atterberg’s writings suggest he valued melody and tradition. Perhaps working with Brahms was a way to connect with the past, or to take on some preservation work. Bolstered with full-bodied strings, the sextet’s newfound dimensions suggest Tchaikovsky’s 1880 Serenade! There are no added effects except for enveloping vibrato and a vaster dynamic range. Supplied with thicker shadows, the slow movement, Poco adagio, glows mysteriously. It’s well known that Beethoven’s shadow fostered Brahms’ initial insecurities where symphonies were concerned. I think we can also hear similar reticence in Brahms’ approach towards string quartets. Compared to the sextets the Op. 51 quartets are constrained and brittle. Even reaching forward to Brahms’ own Op. 115 transcription for just strings, there’s evidence that Brahms was less willing to explore color and texture and was more concerned with rigorous material.

“Strings attached.” Johannes BRAHMS: Sonata for Clarinet and Piano in F Minor, Op. 120, No. 1 (1894; arr. Geert van KEULEN, 2004)1; Sonata for Clarinet and Piano in E-flat Major, Op. 120, No. 2 (1894; arr. KEULEN, 2009)2. Robert SCHUMANN: Fantasiestücke, Op. 73 (1849; arr. KEULEN, 2011)3. Arno Piters1,2,3 (clar), Marleen Asberg1,3, Nienke van Rijn2, Keiko Iwata1,2,3 (vln), Edith van Moergastel1,2,3, Judith Wijzenbeek2 (vla), Benedikt Enzler1,2,3 (vlc), Rob Dirksen1,2 (cbs). Challenge Records CC72572 (1 CD) (www.challengerecords.com). In these tidy arrangements, Keulen asserts that he has adapted the piano parts for strings, introducing small changes to chords and when recharacterizing pianistic passages. Keulen’s faithfulness stifles inspiration, and the strings’ homogeneity trudges along somberly, despite the smart instrumentarium: Op. 120, No. 1 is scored for clarinet with quintet (string quartet plus contrabass), Op. 120, No. 2 is for clarinet plus sextet (two violins, two violas, cello and contrabass). I am not asking for Schoenberg’s xylophone, but surely, if the model is Brahms’ own Op. 115, then there is too much stuffiness. Perhaps it’s the recording balance but the contrabass’ timbre is hard to discern. On the other hand, taking both Op. 120 sonatas together demands gravitas which is delivered in fine form, but where a piano may naturally sparkle, strings need to be instructed to find complimentary timbres. Clarinet and string quartet enable Schumann’s lighter Op. 73 which delights more.

Johannes BRAHMS: Trio for Violin, Horn and Piano in E-flat Major, Op. 40 (1865; arr. Paul KLENGEL, 1919); Clarinet Quintet in B Minor, Op. 115 (1891; arr. KLENGEL, 1904). Christopher Williams (pno). Grand Piano GP749 (1 CD) (www.grandpianorecords.com). Johannes BRAHMS: Clarinet Quintet in B Minor, Op. 115 (1891; arr. Yuri BASHMET). Dmitri SHOSTAKOVICH: String Quartet No. 13 in B-flat Minor, Op. 138 (1970; arr. Alexander TCHAIKOVSKY). Yuri Bashmet (vla), Moscow Soloists. Sony Classical SK 60550 (1 CD) (www.sonyclassical.com). Cast for solo piano, the Horn Trio’s syncopated textures suggest Op. 118’s pieces, whereas the Clarinet Quintet tracks a bit earlier. I miss the horn’s hoot and the natural instrument’s tart tuning. Perhaps because there was already a piano in the trio, this arrangement with chords and passagework acts like a piano opus, whereas the quintet is curious but less effective for keyboard. Like Kirchner, Klengel made a career of arranging (his brother Julius was a cellist). A viola may stand in for clarinet in the Op. 120 sonatas, and so logically, a viola can take the Clarinet Quintet’s wind part. Bashmet’s arrangement expands the string complement to support the viola soloist. It’s not quite a concerto when the viola blends in, or when the ensemble swells. Brahms’ material is sweeter with clarinet. Strings supporting viola tend toward mellowness, sometimes outright gloominess. Was Brahms more concerned with color and harmony in Op. 115? Contrasting with the Zebra and friends release of Brahms’ own strings only quintet arrangement (see above), Bashmet and team navigate a monochrome universe.

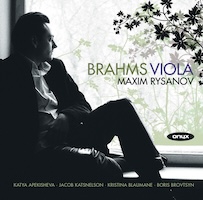

Johannes BRAHMS: Sonata for Clarinet and Piano in F Minor, Op. 120, No. 1 (1894)1; Sonata for Clarinet and Piano in E-flat Major, Op. 120, No. 2 (1894)2; Sonata for Violin and Piano in G Major, Op. 78 (1879; arr. KLENGEL, 1897)3; Horn Trio in E-flat Major, Op. 40 (1865; arr. BRAHMS, 1884)4; Clarinet Trio in A Minor, Op. 114 (1891; arr. BRAHMS, 1892)5. Maxim Rysanov1,2,3,4,5 (vla), Katya Apekisheva1,3,4, Jacob Katsnelson2,5 (pno), Boris Brotsvyn4 (vln), Kristine Blaumane5 (vlc). Onyx ONYX4033 (2 CDs) (www.onyxclassics.com). The Clarinet Trio is one of Brahms’ least familiar chamber works. As with Op. 115 and the Op. 120 sonatas, the work was written for clarinetist Richard Mühlfield in 1891. Brahms adapted the clarinet part for viola himself, and if the original trio is scarce, the viola alternative is rarer (viola, cello and piano). Similarly, a viola can take the horn part in the Op. 40 trio for another unusual threesome (violin, viola and piano). Op. 114 is a talkative work, the non-piano voices continuously interleaving and exchanging ideas. If they are both strings they blend seamlessly. Op. 40 is very different without horn; the viola nearly vanishes inside the piano, and the solo piano transcription is not far away.

A Tchaikovsky, Atterberg, Bashmet, Brahms, de Vlieger, Debussy, Holloway, Karttunen, Keulen, P Klengel, Schumann, Shostakovich, T Kirchner

[More (Dis)Arrangements, Grant Chu Covell]

[More

A Tchaikovsky, Atterberg, Bashmet, Brahms, de Vlieger, Debussy, Holloway, Karttunen, Keulen, P Klengel, Schumann, Shostakovich, T Kirchner]

[Previous Article:

Used Bin Troll Tweets QQQ.]

[Next Article:

Of Coattails, Hangers-On and Human Zoos]

|