A Picture is Worth A Thousand Words

|

Beth Levin and Max Derrickson [September 2022.] Max Derrickson: It’s a pleasure to have the chance to talk with you, Beth! Thank you. You’re a well-known concert pianist with an extremely impressive career. Particularly, your musical heritage with some of the most famous pianists in the 20th century as your teachers (Marian Filar, Leonard Shure and Rudolph Serkin) could be plenty enough for an interview. But if you’ll allow, let’s focus on a specific recital and recording that you are recently doing (in 2022), which includes two very important, and extremely difficult, piano works: Liszt’s Sonata in B minor and Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. Anyone familiar with these works likely knows that they are “bears” to perform — technically, and no less so, musically. And you decided to perform both on one program. Would you talk about your choice of performing these two virtuosic works together?

Beth Levin: Thank you, Max. Lovely to explore the works with you! I think that the Liszt Sonata was really new territory for me and that appealed to me. I had learned the Mussorgsky many years ago and am just now revisiting it. The juxtaposition of the new and the old felt right. Let me say that I’ll be opening the recital with Portrait Miniatures: Three Women by Andrew Rudin which is very much a modern work and a wonderful departure point for the rest of the program. Friends had been urging me to play the Liszt Sonata for quite some time and up to now I resisted it. Suddenly the time seemed right to open the music. From the first read-through I was utterly and completely hooked. Playing through Pictures had more of a nostalgic feel and a reminder in some ways of my Russian/Ukrainian roots (my grandparents on both sides are from Odessa). The music elicits reactions from me as a musician — timing, color, character — that surprise me and I hope will translate to the listeners. In terms of the pieces being difficult, I never like to admit to it. I play for weeks before I realize that I had better isolate and practice those octaves. I recorded the pieces this summer and that was a marvelous education into the music and into the preparation behind the performances. MD: Roots in Odessa! Odessa is like the breadbasket of the world of music. But we can return to that momentarily, as well as to the recording you made this summer. But before we get there: Your programs are always, for me, so challenging and thoughtful… and brave. I have you to thank, actually, for introducing me to Andrew Rudin’s excellent and modern music. It’s intriguing to me that you’re beginning with his three Portraits. Each are under three minutes long, and I gather that they each have a sort of inside joke to them — for example, his dedication of the second portrait to Rose Moss was written for her as a parting gift to her after a summer at the MacDowell artist’s retreat in New Hampshire — and titled To a Wild Moss Rose, which plays (pun-fully and musically) on one of Edward MacDowell’s most famous piano miniatures, To a Wild Rose (Edward, of course, the founder of the MacDowell retreat). How do you see Rudin’s miniatures as departure points to Liszt and Mussorgsky? And, can you say more about your history with this fine composer’s music? BL: Originally, I planned to play Andrew’s work in between the Liszt and the Mussorgsky, and he laughed and said he didn’t mind being sandwiched in the middle of two giants. But I think starting with Portraits makes more sense. They can be likened a bit to the portraits that Mussorgsky paints in Pictures. And I like that the program will begin here and now and work its way back in time which will give the program a path to follow. The Liszt by itself is a vast arc and so the pieces will be arcs within arcs. I simply want the audience to come on the adventure with me. I have played and recorded Andrew Rudin’s work over the years and am very honored that his piano sonata was written for me. MD: I really like the arc idea in your programming here — it sounds like a fun adventure. Regarding the Rudin Portraits, I admire that you are adding this contemporary piece to fit in with Liszt and Mussorgsky on your recital at Merkin Hall in October (October 27, 2022). You also added a contemporary piece on your last CD, playing Disegno No. 3, “Carosello,” (2005) by Swedish composer Anders Eliasson, in between Handel and Beethoven’s colossal Hammerklavier Sonata. Do you have a particular philosophy about performing new music? Also, do you have a particular model, or philosophy, about choosing programs? BL: Sometimes it’s as simple as working on a piece such as the Hammerklavier or the Liszt Sonata and wanting to experience something utterly different. The Rudin for instance is a lovely change from the Liszt when one is practicing, and I think it may work that way for listeners as well. The pieces take over your life for a while and it’s good if you love the music you are working on. A program has to feel right and get one excited — but I’m not sure that I have a philosophy about choosing one. Finally, I really enjoy playing the works of friends — scores that arrive in the mail and are fresh and newly printed, a reminder of when the Liszt and the Mussorgsky were just written. MD: I can completely understand about a piece of music taking over. And so, your method of balancing that out is to play something entirely different. But importantly, I think, as you said, the three short Rudin’s pieces are a wonderful balance to the weightiness of the rest of your program for your concert audience. I can imagine your glee over getting fresh copy in the mail. There’s something delightful about that. Opening the package, feeling the score, first glances and first impressions, and all that wonderful stuff. Do you recall your first impressions of Pictures at an Exhibition? Of Liszt’s Sonata?

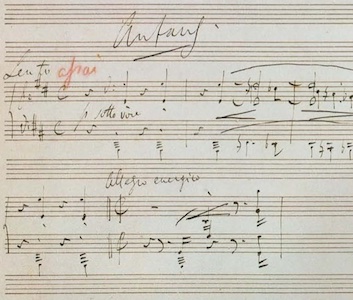

BL: I do remember opening the score to the Liszt Sonata in January and feeling many emotions at once. It was as if the whole work had been in the back of my mind for years just waiting to move to the center. I had to talk to a close musical friend about it and I remember making immediate plans to play it. I had never performed much of his piano music and barely knew anything about the sonata. But I was instantly committed to learning it. Pictures at an Exhibition had been sitting on my shelf for years — I went to it mainly questioning how it would feel to work on it again. I’m surprised at how differently I seem to be approaching the portraits. A kind friend who has heard both versions said he thought I was taking more time now and going deeper into the character. With both the Liszt and the Mussorgsky there is the chance to explore so many artistic facets and create a musical world. But some days I just stare at all the octave passages and technical high jinks. Ha-ha. MD: Looking at the score of the Liszt, and seeing those technical high jinks, some might faint, I think. Perhaps in another interview, we can talk more about relationships with pieces of music — they become such a part of the performer’s life at a certain time — the performer devotes so much heart and psyche to a work, and the score becomes a sort of whiteboard for notes and suggestions, and a reflection of our relationship to the music. Life can get tangled up in a piece of music. We can explore some of that, too, when we talk more about your revisiting Mussorgsky. In the meantime, though, considering those challenging parts of any piece of music, how do you approach conquering them? What’s a typical practice/routine response for you? How have you been tackling the Liszt? BL: The desire to simply play is so strong perhaps because of the extreme expressiveness of the Liszt Sonata. I start out playing a page or so extremely slowly but then the musical sweep takes over and I just have to ride the waves. But in many passages first I practice slowly, evenly, and within a strict context. Speed often comes on its own — you can’t really push. In the octaves I worked out the shapes inherent in the writing and those also seemed to come at their own pace. I worked on the Liszt this morning and it was just that combination of how I will ultimately perform the work with a few moments of “Whoa, Nellie!” Having the recording as a deadline was very helpful, I think. Playing for friends was crucial as well — their suggestions and the mere act of playing through.

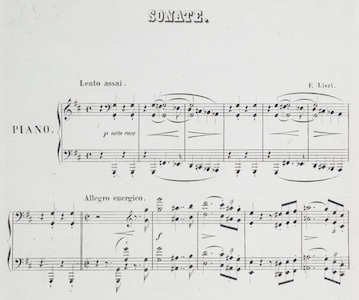

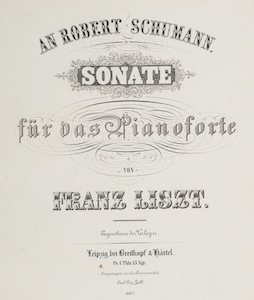

MD: I think Liszt would have appreciated hearing some “Whoa, Nellies!” along the line. And I can only imagine how delightful it must be to be the friend who gets to listen to your putting one of these masterpieces together. Some deeper specifics about the Liszt: Liszt dedicated his Sonata to Robert Schumann as a thank you in reciprocation for Schumann’s dedication of his solo piano work Fantasie in C major, Op. 17 (1839) to Liszt. Liszt completed his Sonata in B minor (in 1853-54), however, after Schumann had been committed to a mental asylum following his attempted suicide. It thus arrived at the Schumann household sans Robert, and found Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms, both virtuoso pianists. As Brahms played through Liszt’s Sonata for Clara, she famously found it rather awful, lamenting that she had “to thank him for that!” — but we should report that it didn’t take long for the Sonata to find its place as one of the great, and one of the most unique, solo piano works of the 19th century. Nonetheless, it’s considered a thorny piece in several regards. Besides its technical challenges, another of those thorns is its rather difficult to categorize, some say genius, hybridization of structural form — somewhere between a true Classical sonata and a Lisztian tone poem. How do you approach this structural uniqueness/ambiguity? Does the arc of the piece let the Sonata dictate its own path?

BL: I lean more to the idea of the work as a tone poem and yet I can see how he structured it as a sonata within a sonata. The Andante sostenuto can be read as the slow movement. Apparently, Liszt said very little about the new form of his Sonata but it certainly influenced composers far into the future. His exquisite themes flow so perfectly and inevitably into one another that you almost feel like he’s taking your hand and saying “just follow me.” I think one can be very free and expressive in one’s interpretation exactly because the structure is so solid. I know that he transcribed Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy for piano and orchestra and may have been very influenced by that same idea of freedom and fantasy within four movements, sort of a Garden of Eden within marble walls. MD: I really do love your description, and it makes sense to me, that Liszt sort of left the mystery out of the mix, clever and again by half. Yet his Sonata carries you along the way, whatever the overall form is. The Garden of Eden within marble walls is a lovely metaphor. I think, too, that inside the Garden also lives a serpent. About Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition: You mentioned above that your “grandparents on both sides are from Odessa.” We won’t confuse Ukraine with Russia, though to be sure, there are connections. Nonetheless, did you feel, and, or do you feel now, that you “hear” the Mussorgsky a little more deeply? And were your grandparents musicians, may I ask? BL: Do you mean was there something in the borscht that gives me the inside track into Pictures at an Exhibition? Seriously, I know that my parents grew up in households where everyone either played the violin, sang or played the piano. Music was a strong element in the lives of my parents and grandparents. But I realize that doesn’t make me an expert on Mussorgsky. I do feel certain instincts for Pictures and I try to be careful about assuming that every instinct is a correct one. I do employ rubato, color, timing and phrasing in ways that I think match and enhance the music and I hope that others will enjoy my interpretation. MD: I think borscht can do a lot of things, but I appreciate the wisdom, and humility, regarding your instincts. Mussorgsky feels, to me, powerful and raw and immensely musical. And so, I’m not sure that one can get too far afield from his intentions once immersed in a performance, do you know what I mean? About the piano version: I (and probably most listeners) have been mesmerized by Pictures since I first heard them, first in Ravel’s orchestral version. It was surprising to me, when I heard the original piano version, how exceptionally well they still sound without all the bells and colors of an orchestra. The music is extremely hardy. Now that you’ve been close to the piano version twice around, do you think Mussorgsky had an orchestration in mind when he was writing Pictures — or do you feel he was truly thinking of the colors of the piano? Are there any favorite moments for you?

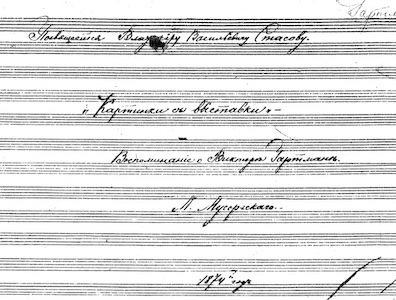

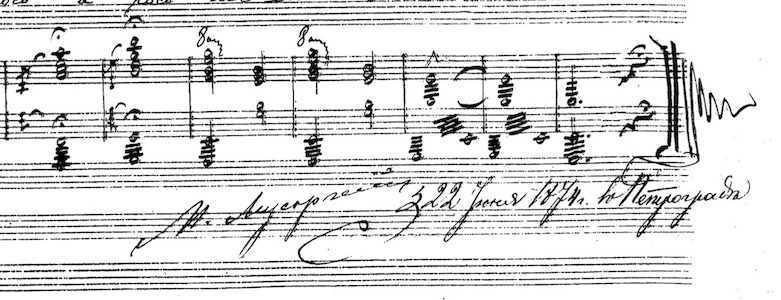

BL: A bit of background: One of Modest Mussorgsky’s best friends was Viktor Hartmann, an artist who tragically died of an aneurysm in 1873 at the age of 39. Two weeks after Hartmann’s death his friends and supporters organized a major exhibition of his works at the Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. About a year later Mussorgsky composed Pictures at an Exhibition. Completed in only twenty days, Pictures was originally a set of short pieces for piano in which Mussorgsky depicted himself walking through the exhibition and contemplating Hartmann’s works. I think Mussorgsky was writing a piano piece — period. He was thinking of the piano as an orchestra at times — complete with bells. But I don’t think he was thinking of orchestration. He knew that the piano is a great chameleon and can recreate almost any vision. One of my favorite “pictures” is Il Vecchio Castello based on an architectural sketch by Hartmann. The melody is so expressive and the rhythmic underpinning so graceful. Also, I appreciate the way that each Promenade is so different from one another. Tuileries was inspired by a now lost crayon drawing of the Tuileries Gardens in Paris. It is so delicate and I love playing it. The Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks is another favorite — my only desire is not to leave too many feathers on the ground. The weightier movements such as Gnome or Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle require the power of a huge sound. I enjoy how Mussorgsky will contrast heaviness with something frothy in the following piece — from an oxcart to a tulle tutu. A favorite arrival point for me is the Sepulcrum Romanum Catacombs. After much activity this piece is slow, austere and as cavernous as a tomb. It may have been an expression of Mussorgsky’s feeling of loss for his friend Hartmann. The music is exhaled in long breaths and marks the point at which Baba Yaga and The Great Gate of Kiev take over and end the work. MD: When one hears a fine performance of this work, I think it’s easy to hear that Mussorgsky was treating the piano like an orchestra at times — which serves to remind us of the extraordinary talent and intellect that Mussorgsky possessed. I love your image of stray notes falling off the keyboard like little chick feathers. And I think it illustrates part of the work’s true genius — its ability to evoke emotions and images. Each picture is a little masterpiece. The Old Castle… what a beautifully expressive tune. And I completely agree that the balancing of heavy and light, the pacing, and the overall direction of Pictures is really a masterful compositional achievement. There are, as we know, only a few of Hartmann’s artworks left to see from that exhibition. And only several of the one’s that Mussorgsky immortalized still exist. I think I’d really love to see the Polish Oxcart and The Old Castle. Which would you really love to see? And do you think seeing them would inform your performance differently? And… do you ever get lost in there… in the Exhibition? That you just want to linger a little while longer at a particular picture? BL: I’d also love to see the Polish Oxcart and The Old Castle. Not seeing the images isn’t necessarily a bad thing and can allow your own imagination to flourish. It reminds me of haiku — better to simply let the words paint a picture, in this case let the music describe the art. Mussorgsky’s great skill as you said becomes so apparent exactly because he is a master at bringing Hartmann’s portraits to life. I think he even goes beyond that and creates an aura, a world in which the art can exist. I think that I do linger here and there in the music when it seems right. I would love the audience to get lost inside the music.

MD: Are there any pictures that you find particularly daunting to play? BL: The final two, The Hut of the Baba Yaga and The Great Gate of Kiev have a few thorny places and they occur in great speed. Speed often magnifies difficulty but what would great music be without challenges? MD: I completely agree with your assessment about Mussorgsky creating a world beyond the art — thinking of the Unhatched Chicks, for example, in Mussorgsky’s wildly wonderful music for that, it rather looks as though Hartmann’s illustration was created secondly, for the music, not the other way around. Regarding the challenges of the last two pictures, now I’m feeling a little guilty. I think you mentioned that you never like to admit something is difficult. Did I just trick you into that? But speaking of challenges, what about the Liszt Sonata? Are there any particular passages that you find really tough? And, though the Sonata is a work that really shows off virtuosity, it also really shines with radiant poetry. Which passages do you find breath-taking? BL: Ha-ha — That’s what makes you a wonderful interviewer! No, I think that dwelling on technical issues such as virtuoso octaves can be insignificant. The genuine task is to present the work as a whole, get inside it, portray what Liszt had in mind, and give a performance. If I miss a few notes or octaves, so be it — that pales in comparison to the actual fulfillment of the work. On the other hand, you need an expressive, flexible and physical technique, but more as a tool, not as an end all. That is probably true for any art. When I’m confronted with a few difficult passages I do laugh at myself knowing that they are merely reminders of imperfection on a path to art. If I get swept away in the Sonata it is where the music melts into pianississimo. For all its grandeur, the poetic passages are truly the ravishing moments in the music. The final Andante Sostenuto is so moving and the final three chords are like a prayer. I hope that the audience feels the emotion of the piece and that I simply express what is there.

MD: I hear you well on that. I think we all have heard when a performance is flawless, technically, but at the cost of being soulless. I’ve never heard any of your performances suffer from that, Beth! And I guess the only thing I can respond to about those beautiful moments, and those last three, heart-stoppingly blissful chords is, “Amen.” Before we start wrapping up our lovely conversation, could you tell us a little more about the recording session that you had for the Mussorgsky and Liszt? And do you know when the CD might be issued? BL: I recorded with old friends Philip Valera (audio engineer) and Mark Peterson (producer) whom I knew at Boston University when I was studying with Leonard Shure and they were both budding organists. We had an easy rapport and were able to kid around when we weren’t doing the more serious work of recording Liszt and Mussorgsky. But I think that is so important when you begin a recording session — the ability to laugh creates a relaxed atmosphere for everyone. There were a few snags: the microphones were nowhere to be found when we first met at ten in the morning on a Wednesday in late May. And the weather in Wilson, North Carolina was extremely humid. The Steinway was freshly tuned but the piano keys were actually damp in Kennedy Hall at Barton College. Not to mention my hair! I don’t yet have a release date for the recording by Aldilà Records. They produced my last CD of the Hammerklavier sonata, Handel and Anders Eliasson, and I was so happy with their dedication to detail. Through the years I guess I’ve learned: If a conductor calls, call back. If a record label wants your mastered CD, just be grateful. MD: The recording engineers that I’ve known are a band of very lovely, smart, laid-back and capable people… and funny. That has to help the recipe in cooking a recording. But damp keys? What on earth do you do about that? (Let’s not even touch the hair subject.) Adilà Records has produced some great recordings. I hope we see yours very, very soon. Allow me, now, to pull way back, and ask you: You have a few years of an illustrious career informing your approach to performing — how might you characterize your playing of these great pieces today, in comparison to when you were, let’s say, in your twenties? BL: I think that I rehearse differently now which affects performance — slower, more thoughtfully. I have always tended to be a bit wild at the piano but after years of playing I have more control of things. Coaching with the conductor Christoph Schluren influenced my playing — as it relates to phrasing, mostly. I think the wisdom from my teachers sort of synthesized for me at some point and now when I look at a score I bring to it more than I did. I wish I could say, “I’m much smarter now.” Ha-ha! I can only hope.

MD: It’s a wonderful realization to recognize your own personal musicianship as a monument to the other great musicians, friends and teachers who shared their talents in the service of the expression of art. Of course, their expertise is wrapped in the gold leaf of your great talents, too. Thanks for that beautiful sentiment, Beth. And thank you for your time and generosity of soul that you’ve shared with me in this interview. Good luck with your recital, and I can’t wait to hear your CD! BL: Thank you so much, Max, for your wise questions. I have enjoyed looking at aspects of the Liszt and the Mussorgsky with you as a guide!

[Max Derrickson has been writing classical program notes and liner notes for orchestras on several continents, as well as recitalists and chamber groups, for over three decades. He was also an orchestral timpanist for 30 years in the Washington, DC area, as well as an ethnomusicological researcher at the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress for several years.]

[More Beth Levin]

[Previous Article:

String Theory 39.]

[Next Article:

Used Bin Troll Tweets KKK.]

|